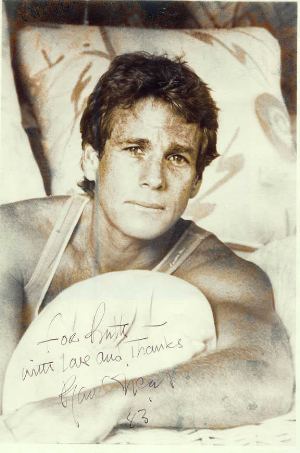

Actor Ryan O’Neal diagnosed with prostate cancer: The famous Love Story actor announces that he’s been diagnosed with the dreaded ‘male’ cancer, even as doubts linger over both prostate cancer vaccine Provenge and PSA blood tests used to diagnose it.

It’s been barely three years since “Charlie’s Angels” star Farrah Fawcett lost died at 62 after losing a three-year battle with anal cancer — and now her long-time boyfriend, actor Ryan O’Neal, has just been diagnosed with prostate cancer.

In an exclusive statement send to People on April 15, O’Neal says, “Recently I was diagnosed with stage 4 prostate cancer. Although I was shocked and stunned by the news, I feel fortunate that it was detected early and according to my extraordinary team of doctors the prognosis is positive for a full recovery.”

O’Neal continued, “I am deeply grateful for the support of my friends and family during this time, and I urge everyone to get regular check-ups, as early detection is the best defense against this horrible disease that has affected so many.”

The 70-year-old actor is no stranger to cancer, having successfully battled leukemia in recent years. His memoir about his life together with Fawcett, “Both of Us,” comes out on May 1.

Prostate cancer is a common cause of death in the United States and Europe and the second most common cause of death from cancer in men of all ages in the U.S. and the United Kingdom. It’s less common in Asia and Africa.

In the U.S., around 240,890 cases were diagnosed and 33,720 men died of it last year. In the UK, some 35,000 men are diagnosed with prostate cancer every year, and around 10,000 will die of it.

A gland found below a man’s bladder that produces fluid for semen, cancer in this gland is rare in men younger than 40.

Problems in passing urine — pain and difficulty starting or stopping the stream or dribbling — as well as low back pain and painful ejaculation, are some of the symptoms of this cancer.

Treatment often depends on the stage of the cancer, determined by how fast the cancer grows and how different it is from surrounding tissue. Surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy or control of hormones that affect the cancer are typical treatments.

Prostate cancer diagnosis and treatments racked by controversy

But unlike other cancers — anal or cervical cancer, as well as breast cancer — where diagnosis and treatment nowadays is pretty much routine and straightforward, prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment has been racking up controversy in recent months.

Late last year, for instance, a United States federal panel concluded that tests done to screen for prostate cancer actually caused men more harm than good.

Doubts loom over prostate cancer vaccine Provenge

Now, a new article by prominent American science writer Sharon Begley details growing controversy over the unique cancer vaccine Provenge — a tale that’s too ‘cloak-and-dagger’ for one involving a cancer and its treatment.

Before the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Provenge for advanced prostate cancer in April 2010, “doctors who raised doubts about it received death threats. Health regulators and lawmakers faced loud protests at their offices. A physician at the American Cancer Society was so intimidated by Provenge partisans that he yanked a skeptical discussion of it from his blog,” writes Begley in a March 30 article for Reuters Health.

While the stormy debates subsided after the FDA approval of Provenge — known chemically as sipuleucel-T — debate has been reignited by a recent disclosure of Marie Huber, a trained scientist and former hedge-fund analyst. Huber claims that the main reason the drug extended prostate cancer survival in clinical trials was that older men in the study who did not receive Provenge died months sooner than similar patients in other studies — and that this was due to a placebo that harmed them. Extending survival was a crucial factor in the FDA’s decision to approve the drug.

When men in the placebo group died earlier because the placebo they received was harmed them, this inadvertently causing Provenge to look better by comparison.

Huber, who has no financial conflict of interest and nothing to gain from her analysis, tells Rueter’s Begley that she’s motivated to help “vulnerable and desperate patients” because the fact that Provenge is harming these men is “utterly horrific.”

“The company got away with hiding data and doctors making US$7,000 per prescription won’t even engage in discussion” about whether it helps their patients, she claims. The former finance analyst, who has earned a double degree in biochemistry and bioscience enterprise from Cambridge University, has made it her mission in the last year to analyze what she believes are deadly flaws in the studies that led to the approval of Provenge by the FDA.

This February, she reported her findings in the prestigious Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Since then, she’s also received threats, Reuters reports — although nothing yet life threatening. One post on an investors’ message board last month suggested that “somebody smack her with a rubber hose.” An email warns her “don’t think you will be unscathed in this battle you waged on Provenge.”

In February, an anonymous commentator on InvestorVillage.com warned that Huber’s work was about to be published “a few days before our earnings. Her agenda is obvious.”

Profits and prestige

There’s profits and prestige at stake. That’s one reason behind the threats against a scientist — which are quite unusual in the medical field. Provenge, Dendreon’s only product, was initially projected to bring in revenues of US$400 million a year. But disappointing sales in 2011 — with product revenues reaching a total of US$213.5 million — has threatened the company’s standing with investors.

Desperation

The other factor behind the threats? Desperate prostate cancer patients themselves. Despite the fact that it’s very expensive (the vaccine costs US$93,000 and patients also have to pay for doctors’ and other charges), that it extends life only by a few months, and its efficacy data is open to interpretation, patients have demanded access to this promising therapy, Begley says.

When the FDA declined to approve the drug in 2007 — after a clinical trial failed to show that it slowed tumor growth — patients protested rowdily. They filed lawsuits and even made death threats against doctors on the FDA advisory panel who didn’t recommend approval, Begley reports.

That kind of fury is fueled by desperation: Most cancers involve pain, but prostate cancer is one that is also so intimately tied to everyday quality of life — when painful urination and painful ejaculation happen daily, these are bound to wear sufferers down. The alternative treatments, too — surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy — are dangerous and have many side effects.

Finally, the patient rampage died down when a pivotal trial called IMPACT — published in July 2010 but shared with the FDA months earlier– showed that Provenge extended median survival by 4.1 months to 25.8 months from 21.7 months. “That was sufficient for FDA approval,” Begley writes.

“Provenge came along when we didn’t have much to offer for prostate cancer,” explains Dr. Len Lichtenfeld of the ACS. “The advocacy community was bursting at the seams for something that worked. When you have that situation, it inflames passions and that can overtake the science.”

First cancer vaccine

Provenge, after all, is a novel approach to the treatment of prostate cancer. “Since it won FDA approval, Provenge has been Exhibit A for the idea that a patient’s immune system can control or cure cancer,” explains Begley in her Reuters report.

The first therapeutic cancer vaccine to reach the market, Provenge works by engineering white blood cells in a patient’s immune system to destroy prostate cancer.

Leukapheresis

“Each dose of Provenge is custom-made. A nurse or technician withdraws white blood cells from a man’s arm in a three-to-four hour procedure called leukapheresis,” Begley explains. Then they go through the following steps:

• The cells are then shipped to a Dendreon facility, where they are incubated for two days with a “fusion protein”– one protein that stimulates the cells’ growth and maturation and another called prostatic acid phosphatase or PAP. This protein, Begley writes, is an “antigen that studs prostate cancer cells like antennae, pieces of it sticking out of the cells’ surfaces.” Dendreon claims that the patients’ white blood cells take up this antigen within hours.

• The cells are then shipped back to the physician

• The doctor infuses these into the patient.

• Inside the body, Dendreon claims that the modified cells trigger the immune system to produce T cells that kill any cell sporting the PAP antigen — or the prostate cancer cells.

• A full treatment includes three such procedures, two weeks apart.

But where’s the evidence?

That should eliminate the cancer — in principle. But in clinical trials, Provenge didn’t shrink either the primary tumor or metastases.

“That raises doubts over whether Provenge helps patients live longer, as the IMPACT trial reported,” Steven Rosenberg of the National Cancer Institute, a leading tumor immunologist points out.

The FDA admits that data supporting Provenge’s approval didn’t show that the drug shrank tumors — it was the reported overall survival benefit that convinced the agency to approve the vaccine. There is a “lack of evidence of anti-tumor activity,” the reason for which “is unclear,” FDA spokeswoman Rita Chapelle tells Reuters, citing data submitted by Dendreon for its approval.

Suspicious survival benefit

Now, the new analysis of Huber showed that men who received the placebo in Provenge trials had very different survival times based on their age.

• Men older than 65 lived 23 months with Provenge and 17.3 months on placebo.

• Men younger than 65 lived 29 months with Provenge and 28 months after receiving placebo.

• The four-month edge in median survival from Provenge for all patients was due to longer survival among older men who got the vaccine.

But this is suspicious, Huber says, pointing out that, “There is no efficacy in the younger patients, the primary group where you would expect it.” Since the immune system weakens with age, an immune-based therapy should work better in younger men, she explains.

Some experts agree with Huber. “If it was really a vaccine, you’d think younger men would show more response, since they are more immunocompetent,” says NCI’s Rosenberg.

Harmful placebo?

Tipped off by this inconsistency, Huber and her co-authors re-analyzed the clinical trial for Provenge and now argue that the placebo used in the trial may have harmed the older men. By doing so, it slashed months off their lives and inadvertently made Provenge seem beneficial. Two prostate-cancer specialists agree with this argument.

One way that could have occurred was through the leukapheresis. According to calculations by immunologist Laura Haynes of the Trudeau Institute, a co-author of the JNCI paper, that process removed about 90 percent of certain kinds of circulating white blood cells. Trudeau is an independent, not-for-profit, biomedical research center in New York.

Huber and her co-authors note that:

• The Provenge men got back about 32 percent of the white blood cells, which had been stored at body temperature.

• The placebo men got back 12 percent of the white blood cells, which had been incubated at near-freezing temperatures.

Cold storage has been reported to kill “most, if not all, of those cells,” the authors write in their paper. What’s more, “if you return dead and dying cells to older men you are likely to cause inflammation,” which can stoke the growth of cancerous cells, Haynes claims.

Peter Iversen, a urologist and prostate-cancer surgeon at the University of Copenhagen and another co-author of the paper with Huber argues further that younger men were better able to replace the lost white blood cells, while the older men could not — resulting in early death. “These cells are very specialized and there is research suggesting that removing them can harm older men,” he says.

Surprisingly, their arguments are backed up by a paid consultant to Dendreon’s IMPACT trial.

“The control vaccine used in IMPACT and in the predecessor trial had never been used anywhere for anything and may well have been detrimental to patients,” says Donald Berry of MD Anderson Cancer Center, a leading biostatistician. “Here’s a great way to get your drug approved: Kill the control patients.”

New analysis is just as flawed

But critics of Huber’s new analysis argue that the number of cells removed during leukapheresis is too small to suppress the immune system. There’s no evidence that the men who received placebos in the trial suffered effects of a depleted immune system or more infections than the men who received Provenge, says Charles Drake, an oncologist and immunologist at Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Oncologist Philip Kantoff of Dana Farber Cancer Center, the scientist who led IMPACT, says his colleagues in immunology “dismissed as nonsense the idea that leukapheresis could hurt individuals.”

Dendreon’s scientists also take issue with the statistics. Analyzing data retrospectively is a statistical no-no, they say — and the FDA agrees, telling Reuters that such post-hoc statistical analyses “are exploratory” and their results “must be interpreted with caution, as acknowledged by the authors.”

Meanwhile, promising new agents for advanced prostate cancer are in the pipeline. These include:

• Oral androgen-inhibitor Zytiga from Johnson & Johnson that won FDA approval in 2011.

• Another oral drug from Medivation Inc. called enzalutamide in the final phase of clinical trials

• A vaccine that targets PSA, from Bavarian Nordic Immunotherapy in late-stage trials.

Prostate cancer tests cause harm

Earlier this year, a federal panel concluded that PSA prostate cancer tests caused more harm to men than good.

The blood test that is currently used to screen for prostate cancer frequently leads to overdiagnosis — prompting men to undergo invasive treatments like surgery that harm them with painful and often life-altering side effects like impotence and incontinence.

That’s what the investigative panel called by the FDA to advise it concluded last October. Its findings were published early this year.

In its report, published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) said prostate cancer treatments leave many survivors with erectile dysfunction, incontinent, and with difficulty urinating and controlling bowel functions. For its report, the panel analyzed five of the largest studies on the PSA tests.

Patients are prompted by a diagnosis made after the blood test to undertake treatments —surgery, radiation or hormone therapies

But the PSA test — a blood test designed to detect higher than normal levels of prostate-specific antigen, or PSA, in the blood — is becoming increasingly controversial as more doctors and studies cast doubt on its effectiveness.

For one, a high PSA level can signal prostate cancer but it can also indicate conditions that are more benign.

Now the USPSTF says that 20-30 percent of all men who get radiation therapy or surgery experience incontinence and impotence.

What’s worse, the experts’ panel said that in one European study it analyzed, the rate of overdiagnosis from PSA screening was estimated to be as high as 50 percent. Based on that study, if 1,410 men are screened, 48 will be found candidates for treatment—but just one life will be saved from prostate cancer.

Surprisingly high rates of hospitalization for bloodstream infections after prostate biopsies — as well as a 12-fold greater risk of death in those who develop these infections were found by a recent Johns Hopkins University study.

The USPSTF concludes: the benefits of the PSA test appears minimal, while the downsides are considerable. “The vast majority of men who are treated do not have prostate cancer death prevented or lives extended from that treatment, but are subjected to significant harms,” it says.

Aside from Ryan O’Neal, other famous men who were diagnosed with prostate cancer include: Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu (who was successfully treated of the disease), Australian rules footballer Sam Newman, golf Hall-of-Famer Arnold Palmer, Hollywood royalty Robert de Niro, New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani, former Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau, and several others.

RELATED READINGS:

Prostate Cancer Robotic Surgery

Side Effects of Avodart Prostate Cancer Drug

Can Viagra Prevent Prostate Cancer?